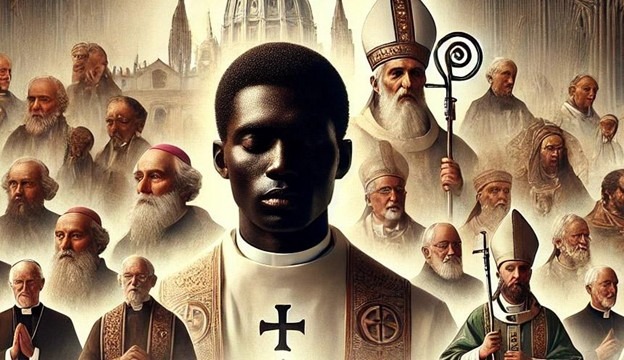

The Classical Tradition Within African American Culture: March/April/May 2025 by Fr. Matthew Hawkins

-

-

Discover the Deeper Story Behind African American CultureCurious about the powerful forces that have shaped African American history and identity? Step into The Classical Tradition Within African American Culture—a journey through thought-provoking reflections by Fr. Matthew that reveal the artistic, intellectual, and spiritual values that have strengthened families and communities for over 400 years. Explore how unity of thought and feeling, the path from fragmentation to wholeness, the link between racial identity and universal humanity, and the yearning for eternity have woven a deeper story—one that continues to inspire today.

Fr. Matthew Hawkins

-

-

-

From Fragmentation to WholenessMay 4, 2025The Healing Power of Faith in the African American TraditionThe story of African American history is, in many ways, a story of fragmentation—of lives broken by slavery, families torn apart by systemic injustice, and communities shattered by racism and oppression. Yet, through this history of suffering, there emerges a powerful testimony of wholeness and restoration. The African American classical tradition, expressed through music, storytelling, sermons, and faith practices, is not simply about surviving fragmentation—it is about transforming that brokenness into a coherent, life-giving whole.

This journey from fragmentation to wholeness mirrors the very heart of the Christian narrative. The story of salvation is not one of avoiding suffering but of Christ entering into human brokenness to bring healing and restoration. In the same way, the African American tradition reveals how faith can gather the scattered pieces of pain, memory, and struggle and weave them into a living testament of resilience, dignity, and hope.The Fragmentation of the Human Experience and the Biblical Story

In Scripture, fragmentation begins with the fall of humanity. The story of Adam and Eve reveals how sin fractures the unity between God, humanity, and creation itself. From that point forward, the Bible is filled with stories of division and exile—Cain and Abel, the Tower of Babel, the Israelites’ enslavement in Egypt, and the exile in Babylon. Fragmentation is not just physical; it is spiritual, emotional, and communal.

But God’s response is always to restore, to gather what has been scattered, and to heal what has been broken. The prophetic words of Ezekiel ring true for all who feel dismembered by life’s hardships: “I will gather you from the nations and bring you back from the countries where you have been scattered”(Ezekiel 11:17). The African American experience echoes this biblical theme—a people scattered and fragmented by injustice, yet drawn together by a God who promises restoration.The African American Tradition: Weaving Fragments into Wholeness

The beauty of the African American classical tradition lies in its ability to transform the fragments of history into a coherent, sacred narrative. Spirituals and gospel songs often carry themes of deliverance and unity. Songs like “There Is a Balm in Gilead” and “We Shall Overcome” do not deny suffering; instead, they proclaim healing and hope. These songs take the fractured pieces of historical trauma and weave them into testimonies of endurance and faith.

This movement from fragmentation to wholeness is not just artistic—it is theological. Every time a fragmented melody resolves into harmony, or when a sermon draws together themes of suffering, redemption, and joy, the African American tradition reflects the deeper spiritual truth that God brings order out of chaos. This is what St. Paul reminds us in Romans 8:28: “We know that all things work together for good for those who love God.” The tradition affirms that the scattered pieces of our history, when offered to God, can be transformed into a masterpiece of grace and redemption.

In this way, the African American classical tradition stands as a living witness to the power of God’s grace at work in human history. It reveals that even in the face of fragmentation, a deeper unity is possible—one that is forged not by forgetting the wounds of the past but by offering them to the One who alone can heal. Just as Scripture tells the story of a broken humanity restored in Christ, so too does the African American experience testify that the journey from suffering to wholeness is not only possible but beautiful. It is a testament to the truth that in God’s hands, no fragment is wasted, and every story of pain can become a song of redemption.

-

The Classical Tradition of African American CultureApril 27, 2025A Journey of Faith and Understanding

Too often, African American worship traditions are misunderstood as purely emotional—marked by heartfelt music, passionate preaching, and vibrant expressions of praise. But this classical tradition is far more than emotionalism. At its core, it reflects a sacred movement: from raw human feeling toward wisdom, from heartfelt cries to divine understanding. In other words, emotion is not the destination—it’s the doorway.The African American classical tradition invites us into the deep spiritual truth that God meets us where we are—often through our emotions—but He never leaves us there. Through our worship, especially in song and sermon, God draws us toward greater reflection, understanding, and transformation.

Too often, African American worship traditions are misunderstood as purely emotional—marked by heartfelt music, passionate preaching, and vibrant expressions of praise. But this classical tradition is far more than emotionalism. At its core, it reflects a sacred movement: from raw human feeling toward wisdom, from heartfelt cries to divine understanding. In other words, emotion is not the destination—it’s the doorway.The African American classical tradition invites us into the deep spiritual truth that God meets us where we are—often through our emotions—but He never leaves us there. Through our worship, especially in song and sermon, God draws us toward greater reflection, understanding, and transformation.

Consider the sorrowful strains of a spiritual like Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child. Its grief is not just personal—it becomes communal, resonating through the congregation as a shared lament. This is where the beauty of the tradition shines: the emotion stirred in the heart opens the mind to consider the dignity of human life, the pain of suffering, and the hope offered by divine compassion. What begins as a cry of the soul becomes an invitation for the intellect to wrestle with the truths of the Gospel.

In Scripture, the heart is described as the wellspring of wisdom. “With all your getting, get understanding,” says Proverbs 4:7. The classical tradition embodies this scriptural call by joining heart and mind. A moving homily or stirring gospel hymn is not meant to stop with emotion—it is meant to lead us deeper, to ask: What is God teaching me through this?What truth is hidden beneath this feeling?

Jesus teaches us in the Shema (Matthew 22:37) to love God with all our heart, soul, and mind. True worship is never just emotional or just intellectual—it is holistic. The African American tradition, when embraced fully within Catholic liturgy, reveals this beautifully. It shows how the fire of emotion can light the path to understanding. Worship becomes not only expressive but formational.

The great preachers of the tradition—Howard Thurman, Martin Luther King Jr., and others—did not rely on emotional appeal alone. Their preaching was steeped in Scripture, theology, and moral reasoning. It stirred the heart and sharpened the mind. In the same way, our Catholic faith calls us to “faith seeking understanding,” as St. Anselm wrote. The homily, the hymn, the shared prayer—all are meant to awaken not just feeling, but thoughtful reflection on God’s truth.

This is the gift of the African American classical tradition: it reminds us that God speaks through the heart, but also through the mind. Emotion is not the opposite of understanding—it is the path that leads to it. When we allow our worship to touch both heart and intellect, we draw closer to God in the fullness of love: with all our heart, soul, and mind.

Let us not leave our feelings at the door of the church. Let them lead us—to reflection, to learning, and to the wisdom that transforms us in Christ.

-

-

-

The Classical Tradition and African American SpiritualsMarch 16, 2025

The Classical Tradition of the Spirituals—Songs of Humanity and Dignity

One of the great treasures of the Christian tradition is the power of sacred song to express deep truths about the human experience. In the classical tradition of the arts and literature, themes of exile, suffering, and the struggle for dignity have always resonated across time and cultures. The Spirituals, which emerged from the crucible of enslavement and racial discrimination, are no exception. These songs do more than recount the suffering of Black Americans—they connect those experiences to the universal human longing for freedom, dignity, and the recognition of our shared humanity.

One of the great treasures of the Christian tradition is the power of sacred song to express deep truths about the human experience. In the classical tradition of the arts and literature, themes of exile, suffering, and the struggle for dignity have always resonated across time and cultures. The Spirituals, which emerged from the crucible of enslavement and racial discrimination, are no exception. These songs do more than recount the suffering of Black Americans—they connect those experiences to the universal human longing for freedom, dignity, and the recognition of our shared humanity.

Like other great works of literature, the Spirituals seek to break down barriers that deny human dignity, awaken the interior life of the individual and the life of the mind, and even confront the fear of death itself. For those who first sang these songs, the fear of death was not merely about physical mortality; it was the fear of living without meaning, without hope, without the assurance that they were seen and loved by God. The Spirituals, then, became a bold act of defiance—songs of survival, resistance, and divine hope.

Take, for example, the song “I Got Shoes.” The lyrics proclaim, “I got shoes, you got shoes, all God’s children got shoes.” To those unfamiliar with its context, it may seem like a simple song of celebration. But for enslaved people who were often forbidden from wearing shoes—a mark of status and equality—these words were radical. They declared that no matter what society said, their dignity came from God alone. Though their humanity was denied in the eyes of the world, they knew they were children of God, clothed in His grace and bound for the kingdom where their dignity would be fully revealed.

Similarly, “Follow the Drinking Gourd” was more than a coded map to freedom on the Underground Railroad. It carried profound spiritual meaning, much like the Israelites following the pillar of fire through the wilderness. It reminded those who sang it that God’s guidance was ever-present, that salvation was both a physical and spiritual journey and that faith required courage and perseverance that transcended life itself. Those who followed the “drinking gourd”—a reference to the North Star—understood that their journey was not just about escaping physical bondage but living for eternity.

These songs, and many others like them, do not reflect a theology of resignation or passive waiting for justice in the afterlife. Rather, they proclaim a faith that is alive and gives calmness, strength, and perseverance in the face of suffering. The Spirituals remind us that the world does not give us our dignity—it is inherent in every person because we are made in the image of God.

These songs call us to faith, hope, and perseverance, even when life presents us with many challenges. They proclaim that no matter what trials we endure, God’s promise remains, and His justice prevails through our inner strength, reason, and willingness to cooperate with God’s plan. We must carry this spirit of dignity in our lives, walking in faith with the courage and self-respect of those before us whom the Spirituals inspired.

-

Mystery, Tradition, and the Sacred Art of Preaching in the Catholic ChurchMarch 9, 2025

Preaching in the Catholic Church is more than a moment of inspiration—it is an intellectual, historical, and spiritual discipline rooted in mystery, mastery, and tradition. The rich tradition of African American sermons, with their depth, cadence, and scriptural power, embodies this classical tradition, not as mere emotional intonation but as a vehicle for education and spiritual formation. Bible studies and homilies at St. Benedict the Moor are not departures from Catholic heritage but vital expressions of it. They link African American heritage to the broader universal themes of faith and human experience.

Preaching in the Catholic Church is more than a moment of inspiration—it is an intellectual, historical, and spiritual discipline rooted in mystery, mastery, and tradition. The rich tradition of African American sermons, with their depth, cadence, and scriptural power, embodies this classical tradition, not as mere emotional intonation but as a vehicle for education and spiritual formation. Bible studies and homilies at St. Benedict the Moor are not departures from Catholic heritage but vital expressions of it. They link African American heritage to the broader universal themes of faith and human experience.Mastery and Discipline in the Art of Preaching

The great preachers—whether in the Catholic, Orthodox, or Protestant traditions—have always approached homiletics as a discipline requiring years of study, prayer, and practice. St. Augustine, St. John Chrysostom, and St. Bernard of Clairvaux were masters of rhetoric, steeped in Scripture, philosophy, and theology. Similarly, the African American preaching tradition has been shaped by generations of disciplined scholars and pastors who devoted their lives to understanding the Word of God. It is not simply a matter of passion or vocal dexterity; it is a structured form of intellectual and spiritual engagement that requires deep study of Scripture, historical context, and the lived experience of the people of God.

This tradition is visible in Bible studies as well, where exegesis—interpreting Scripture within its proper theological and historical context—is emphasized over mere personal opinions or isolated emotional responses. The Catholic homiletic tradition, when practiced with integrity, is a blend of biblical literacy, theological reflection, and oratory skill, ensuring that the Word of God is proclaimed with both power and precision.Mentorship and Education: Passing Knowledge to Future Generations

Preaching and Bible study are not solitary endeavors but communal and generational ones. Homilies should not simply inspire—they should teach and mentor, forming new evangelists among the clergy, the religious, and the laity, who will carry forward the sacred task of breaking open the Word of God. In the African American tradition, preaching has always been a means of passing down wisdom, shaping young and old minds, and forming people in moral and spiritual discipline.

This reflects a long-standing tradition of structured theological education, from the catechetical schools of the early Church to modern seminaries and lay formation programs. Preaching and Bible study are about ensuring that the faith is handed down intact, with clarity and integrity, from one generation to the next.Connecting Black Cultural Expression to Universal Themes

When a priest or deacon proclaims the Gospel, it is not simply a cultural moment—it is a continuation of the prophetic witness of the Church throughout history.

This is why homilies at St. Benedict the Moor are not just about emotional highs but about connecting the sacred text to the lived realities of our community. The daily struggles, the hope for redemption, the call to holiness—these are not just Black experiences; they are human experiences, and they are central to the mission of the Church.Commitment to Structure and Tradition

In a world where preaching is sometimes reduced to entertainment or self-promotion, the Catholic tradition calls for something deeper: a commitment to the integrity of the Word. The homily is not about the preacher’s personal opinions or charisma but about faithfully communicating the Gospel. While the African American homiletic tradition is rich in expression and engagement, it is ultimately rooted in the same structure that has guided Catholic preaching for centuries—a careful reading of Scripture, alignment with Church teaching, and an emphasis on leading people to deeper faith and discipleship.

-

-

-

Mastery, Tradition, and the Sacred Sound of Gospel Music in the LiturgyMarch 2, 2025

Music in the Catholic liturgy is not mere entertainment; it is prayer, proclamation, and participation in the mystery of God. Within the African American tradition, the rich legacy of spirituals and gospel music reflects not only deep emotion but also an intellectual, historical, and spiritual tradition rooted in mastery and discipline. Too often, gospel music is viewed through a purely romanticized or commercialized lens, reduced to its emotional power rather than recognized as an inheritance of structured artistry, mentorship, and theological depth. In our worship at St. Benedict the Moor, we celebrate this music not as a performance but as an embodiment of faith, discipline, and tradition, linking our heritage to the broader Catholic and universal Christian experience.

Music in the Catholic liturgy is not mere entertainment; it is prayer, proclamation, and participation in the mystery of God. Within the African American tradition, the rich legacy of spirituals and gospel music reflects not only deep emotion but also an intellectual, historical, and spiritual tradition rooted in mastery and discipline. Too often, gospel music is viewed through a purely romanticized or commercialized lens, reduced to its emotional power rather than recognized as an inheritance of structured artistry, mentorship, and theological depth. In our worship at St. Benedict the Moor, we celebrate this music not as a performance but as an embodiment of faith, discipline, and tradition, linking our heritage to the broader Catholic and universal Christian experience.Mastery and Discipline in the Sacred Art of Music

The African American musical tradition is a classical tradition in its own right, built upon the mastery of voice, harmony, rhythm, and theological reflection. Those who shaped spirituals and gospel music did so through structured creativity and deep religious insight. The call-and-response, improvisation, and syncopation found in gospel music are not accidental but cultivated through years of practice and refinement, much like the discipline of Gregorian chant or polyphony. This mastery is evident in our liturgical music, where every note, every repetition, and every crescendo is crafted to serve the deeper purpose of drawing the congregation into an encounter with God.Mentorship and Education: A Sacred Legacy

Music is one of the primary ways we pass down wisdom and faith to future generations. In the African American church tradition, singers and musicians do not simply play an instrument or lift their voices without guidance. They are mentored, learning both the technical skills of music and the spiritual weight of their role in leading worship. This reflects the Church’s long-standing tradition of passing on sacred knowledge through apprenticeship—whether in monastic chant, classical composition, or liturgical leadership. The gospel tradition in Catholic liturgy is not a break from this model but a fulfillment of it, forming musicians and worshippers alike in the discipline of prayerful song.Connecting Black Cultural Expression to Universal Themes

African American spirituals and gospel music are deeply rooted in particular historical experiences—struggle, deliverance, hope, and perseverance. Yet, they also express universal human themes. When we sing “Lift Every Voice” or “Precious Lord, Take My Hand,” we do not simply recall our own history, but we enter into the biblical story of Exodus, the Paschal Mystery of Christ’s suffering and resurrection, and the universal human longing for redemption. This is the same impulse that led medieval monks to chant the Psalms, the same spirit that guided composers of the Latin Mass. Our music, then, is not isolated from the broader Catholic tradition but in profound harmony with it.A Commitment to Structure and Tradition

In a world that often prizes novelty and entertainment over tradition and depth, the liturgical use of gospel music in the Catholic Church stands as a testament to the power of rootedness. Ours is not a tradition of improvisation for improvisation’s sake nor of emotion without theological depth. It is a tradition of prayer that has been tested, refined, and handed down. When we sing the Gloria or the Agnus Dei in gospel style, we are not departing from Catholic liturgical norms but enriching them with the voice of a people who have suffered, endured, and hoped in the God of salvation.

At St. Benedict the Moor, our music is more than sound—it is an offering of mastery, tradition, mentorship, and faith. It is a bridge between the African American experience and the universal Church, a sound that echoes through history and will guide future generations in worship. Let us continue to sing with understanding, reverence, and joy, knowing that through music, we participate in something far greater than ourselves—the living tradition of faith that leads us to God.

-